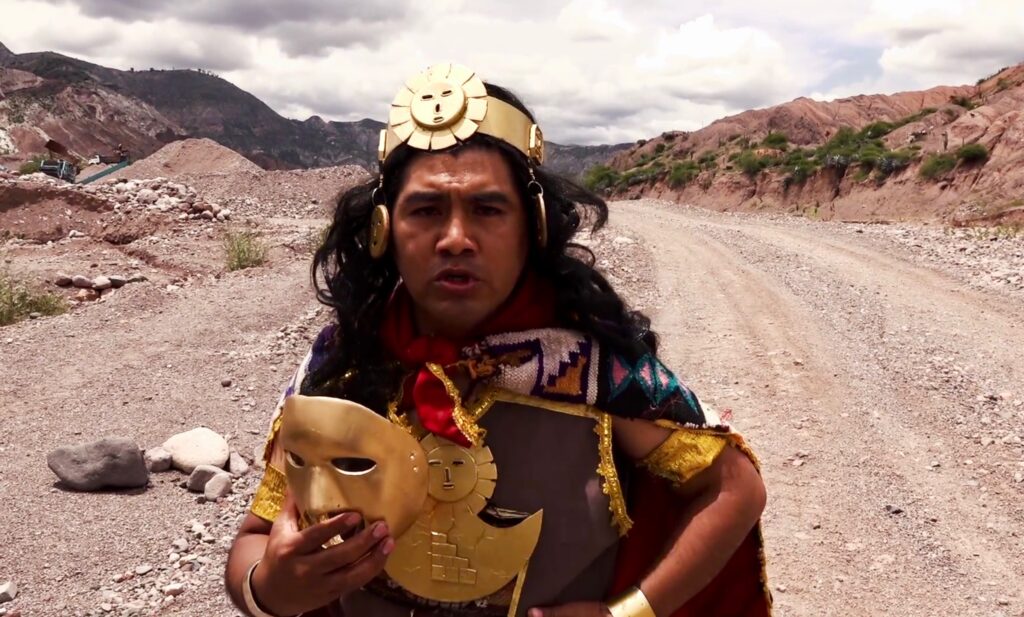

Horror in the Andes, a short documentary by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich, looks behind the scenes of a blood-drenched film adaptation of an ancient Inca tale: The Curse of the Inca. Dozens of similar low-budget horror films have been made in the Peruvian region of Ayacucho over the past few decades. Prior to the screening of her documentary on Saturday, November 1st, at 2:15 PM at Imagine 2025, Dietrich will elaborate on the socio-political context of these hyper-local genrefilms. The event is part of our theme programme Reversing the Gaze – Reclaiming history with Indigenous Fantastic Cinema. We spoke briefly with Dietrich about her work.

Dietrich, an Austrian-Peruvian anthropologist, stumbled upon the Ayacuchan horrorfilm scene during a visit in 2016. ‘I saw an enourmously long queue outside a cinema. I bought a ticket out of sheer curiosity and have been hooked by Ayacuchan horror ever since.’ Back then, she saw The Pink House (La casa rosada), which was based on a true story of violence and torture inflicted by the Peruvian state forces during the internal armed conflict (1980 – 2000). ‘The audience was really diverse: there were even five-year-olds in the room! Films like The Pink House are screened regularly, and they always sell out. It touches a nerve with the community here, who feel marginalised when it comes to telling stories for the big screen.’

Marginalised and also stigmatised, as the Ayacucho region was long associated with terrorist movement Shining Path. When the movement was largely dismantled in the 1990s, it was time to work through the trauma. A younger generation started working with video and found horror to be an ideal outlet.

The past three decades have each had their own focus. Dietrich: ‘In the nineties, many of the films were about recent armed conflict, a genre-subset that’s known as violencia social. When those stories were done, cautionary tales emerged, about not going out when it’s too dark or not trusting strangers. Now, the focus is shifting back more towards colonial stories from the time of the Incas and the Spanish invasion. The Curse of the Inca is an example of that trend.’

Incidentally, only a tiny percentage of the films make it to their final act. Dietrich: ‘The ambition to actually finalise a film is there, but most of the time they lack funding and support. That’s when you see makers come together to watch and discuss single scenes. It’s kind of a social event.’ At the end of Horror in the Andes, this practice is visualised strikingly: a sheet serves as a projection screen in a living room, with family and friends watching.

The documentary certainly piques curiosity about the Peruvian horrorfilms themselves. But will they ever find their way to international festivals, let alone film markets? Dietrich: ‘There’s plenty of creativity and drive, but there’s insufficient training, no infrastructure, no funding. And that, in turn, is a consequence of current Peruvian cultural politics. With their films, these filmmakers are asking for attention, respect, and support from the Peruvian film industry. And there are international opportunities, too; no better genre than horror to get people excited, right? The best thing would be for producers to come to Ayacucho and help the people here make great films, so that the policymakers in Lima can finally see what they’re worth.’